The cycle of deaths and resurrections of Chico da Silva

by Andrea Bellini

Visionary and cosmogonic, Chico da Silva‘s art has retained its force over time; what has changed is the way we look at it, confirming that it is not the work of art that is exposed to the public, but the public – with its own cultural categories – that is exposed to the work of art.

The story of this extraordinary Brazilian artist can serve as a breviary for all possible Western misunderstandings of the so-called New World, which – as we know – is as old as our own. Chico da Silva has long been considered a paradigmatic figure of indigenous Brazilian art, that is, of a unified style and aesthetic that never existed as such, except in the European imagination. According to this interpretation, da Silva is an indigenous artist who paints bizarre animals in primitive style, immersed in mythical, untamed nature. Da Silva has never claimed an indigenous identity for his work, however, and has explicitly stated that the subjects of his paintings are

not memories of his childhood in the Amazon, but the product of his imagination. The Brazilian artist’s is in fact an original pictorial language, capable of expressing a singular universe through the use of unusual techniques.

Born in 1922 or 1923 and raised in the Amazon rainforest in the north-western state of Acre, da Silva lost his father, a Peruvian-born fisherman, to a rattlesnake bite as a child. In the early 1930’s, he moved with his mother to Pirambu, one of Fortaleza’s poorest districts. It was here that he began to draw large-beaked birds, monstrous fish and ghost ships incharcoal on the walls of fishermen’s houses. In 1943, Jean-Pierre Chabloz, a Swiss artist who had recently settled in the area, saw the drawings while strolling through the streets of the neighborhood and was impressed.

After some research, he met the young self-taught artist and encouraged him with paper, ink, gouaches, pencils and brushes. During the five years he lived in Brazil, Chabloz promoted his work, placing it in various local and national exhibitions, and looking after its market. However, Chabloz’s support came to an end in 1948, when he returned to Europe. Unsure of how to support himself, da Silva stopped painting for twelve long years, devoting himself to a variety of trades: shoemaker, clog maker, umbrella repairman, barber and cabin boy on fishing boats.

Things changed again in 1960, when Chabloz settled permanently in Brazil. Chabloz not only convinced him to resume his painting, but also managed to get him hired at the art museum of the Federal University of Ceará. For a few years, between 1961 and 1963, thanks to a fixed salary, his protégé was finally able to devote himself entirely to art.

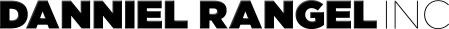

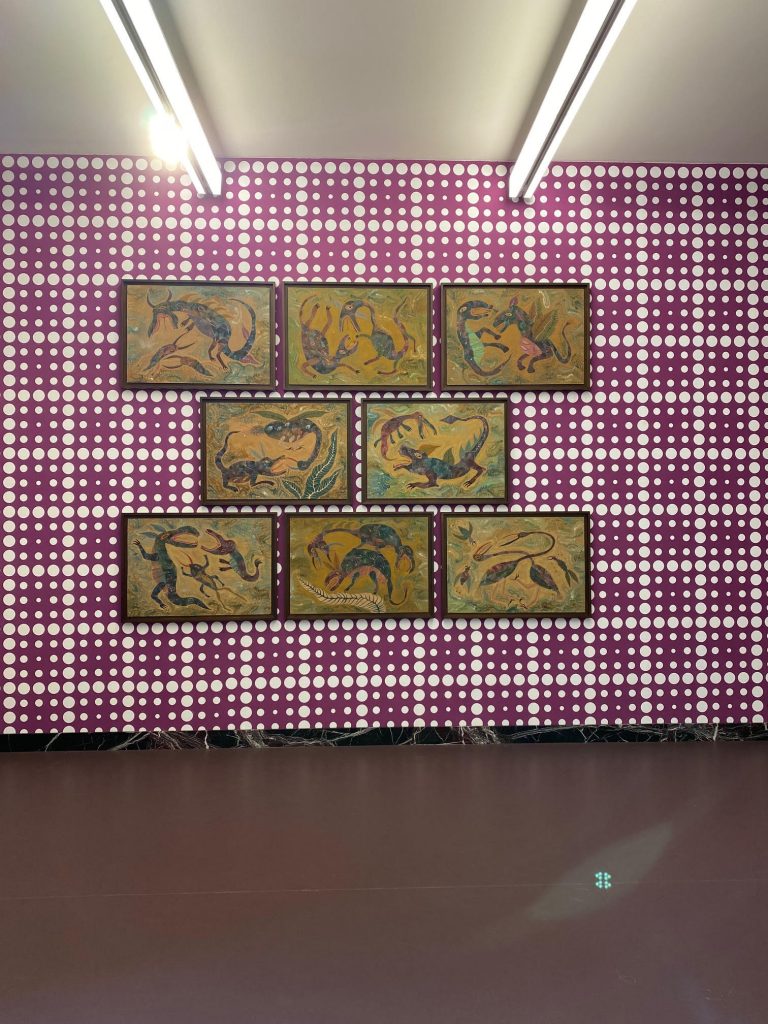

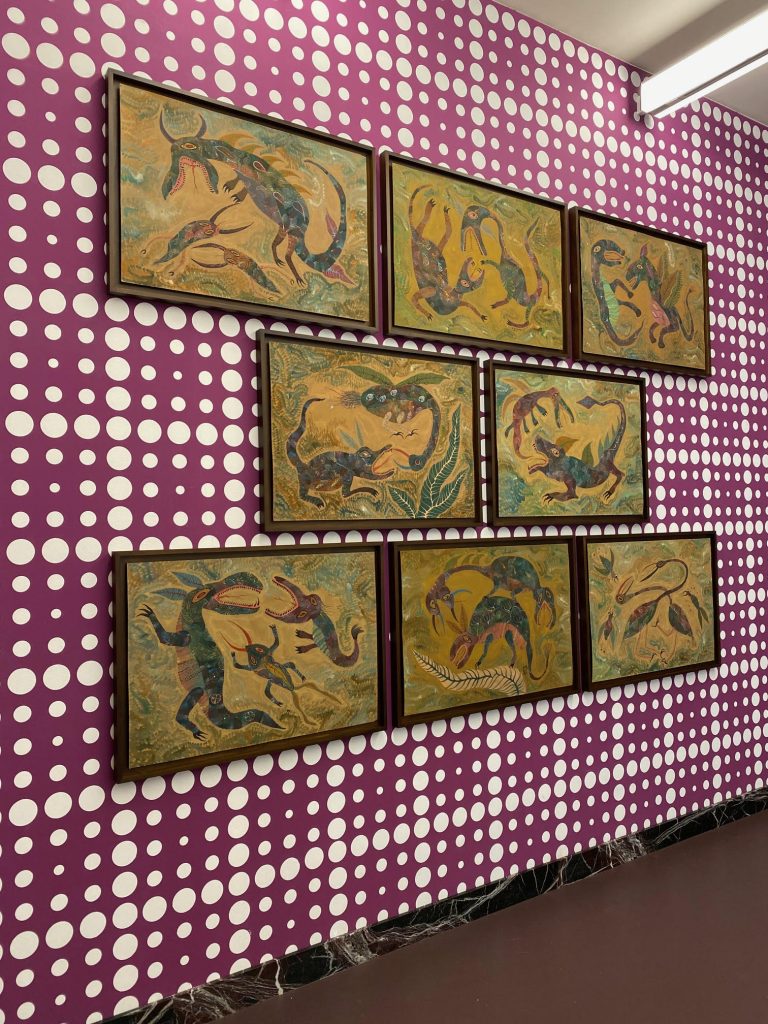

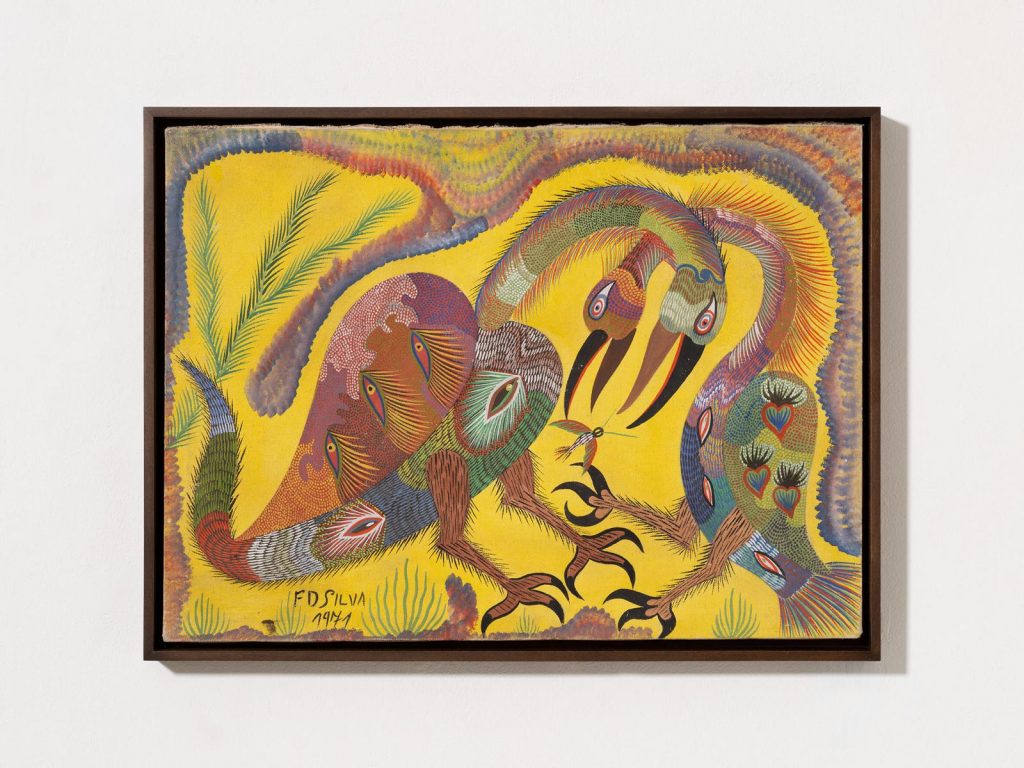

From a pictorial language perspective, da Silva matured a series of formal solutions already defined in the early 1940’s: the application of color without gradation, the pointillist technique, the absence of three-dimensional depth, the creation of rhythm and the visual orientation of the work through the drawing of long and short lines. The iconography is enriched by bizarre anthropomorphic beings and mythological animals, always depicted with mouths wide open from which a forked tongue protrudes.

When, in the mid-1960’s, his work gained notoriety in Brazil and demand for his work grew rapidly, Chico da Silva left the institution to set up his own “workshop”: the Pirambu School was born. The members of the school were four young local men: Sebastião Lima da Silva (Babá), José Claudionor Nogueira (Claudionor), Ivan José de Assis (Ivan), José dos Santos Gomes (Garcia) and his daughter Francisca da Silva (Chica). Da Silva taught them the trade and organized a collective work method. He, Claudionor and Ivan took care of the drawings; Babá, Ivan and Garcia were responsible for color, pigmentation and stippling; finally, Chico da Silva took care of the finishing touches. He then affixed his signature (or “logo”) to the paintings, which he sold directly. Thanks to the contributions of his pupils, the

master’s imagination expanded and his animal repertoire grew. Roosters, herons, jacanas, owls, snakes, flowers, butterflies, pets and small insects now appeared in his compositions.

In 1965, he was invited to represent Brazil at the 1966 Venice Biennale and received an honorable mention from the jury. Two years later, some of his largeformat works were exhibited at the São Paulo Biennale.

His international success coincided, however, with a public controversy that had dramatic repercussions on his health and his art.

It was in 1967 that his first mentor and supporter, Jean-Pierre Chabloz, wrote a highly polemical article in which he declared that most of da Silva’s works in circulation were fake and pictorially modest. Chabloz’s stance, followed by an aggressive and disparaging press campaign, led to the collapse of da Silva’s market. Once again, the Western view on the question of authenticity and originality is far from that of the Brazilian artist: in his school, a technique is transmitted and works are produced collectively, they are not fakes. Traumatized by the controversy, the artist was hospitalized several times between 1970 and 1977 for his alcohol addiction and nervous

breakdowns.

Unwillingly trapped in a continuous cycle of death and resurrection, Chico da Silva’s new life began a decade after Chabloz’s article. The rebirth took place in 1977, thanks to the initiative of a group of intellectuals led by artist and researcher Hélio Rola, who proposed – as part of an exhibition in Ceará – a performance entitled Homens trabalhando. Presented as a conceptual work, the performance consisted in the creation of a large canvas in front of an audience by the five artists of the Pirambu school, under the aegis of their master. Painted in seven days, Homens trabalhando is an emblematic work of Brazilian art of the second half of the 20th century, which has the merit of presenting the school as a collective art phenomenon, a place of experimentation and expansion of the imagination, and not as a center of counterfeiting. Partially rehabilitated by this performance, Chico da Silva returned to an individual practice in 1978, abandoning works on paper and beginning to paint exclusively on canvas.

This exhibition at MASSIMODECARLO Pièce Unique represents a rare opportunity to see a significant body of work by Chico da Silva in Europe, a visionary creator of worlds of diverse fortunes, who deserves a place of honor in the history of Latin American art in the second half of the 20th century.